Tackling racism in Visual FX

Raqi Syed, a writer, visual effects designer and researcher, explores the inherent bias and racism that is reflected across the spectrum of visual effects in global popular culture.

Raqi Syed and Dr Missy Molloy challenge us on the racial and colonial aspects of the increasing use of digital representations of people in film.

“The story our most enduring myths tell us is that a great white man will fall from the sky and save us. Such stories offer audiences very little agency. For meaningful change to happen, we must re-evaluate our ideas not only of greatness, but who we perceive as embodying greatness.”

With a focus on the visual effects industry, Raqi is interested in how the digital human encapsulates these concerns.

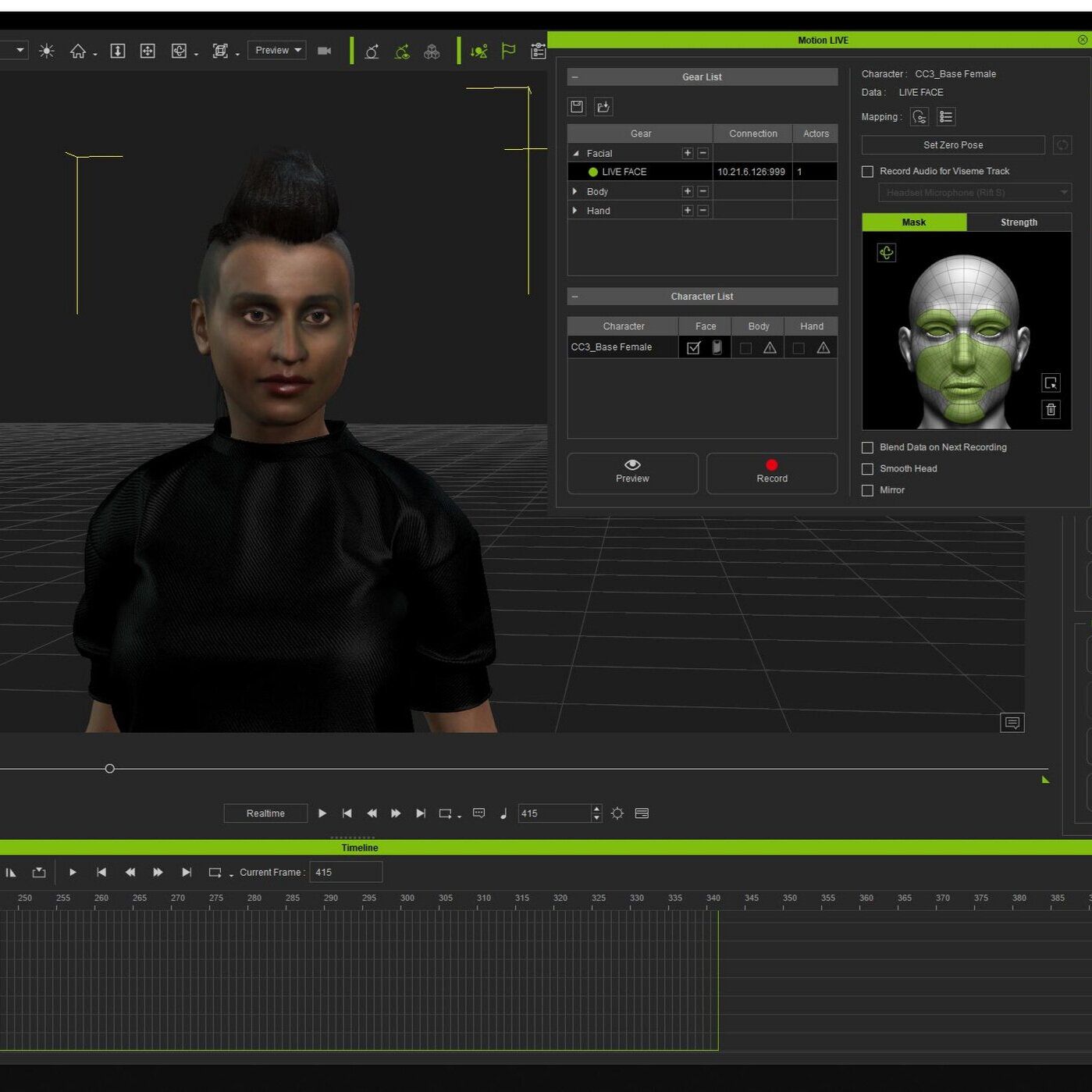

“A digital human means different things to different people—it can be a corporate virtual assistant, a stunt double for a film actor, or a character driven by machine learning in an open-world video game. The idea of a virtual human is something that scientists have been thinking about for a long time and it holds a lot of interest for visual effects designers. Increasingly the digital human is a vehicle for storytelling.”

In this context, Raqi believes that the key question to ask is who gets to be a digital human?

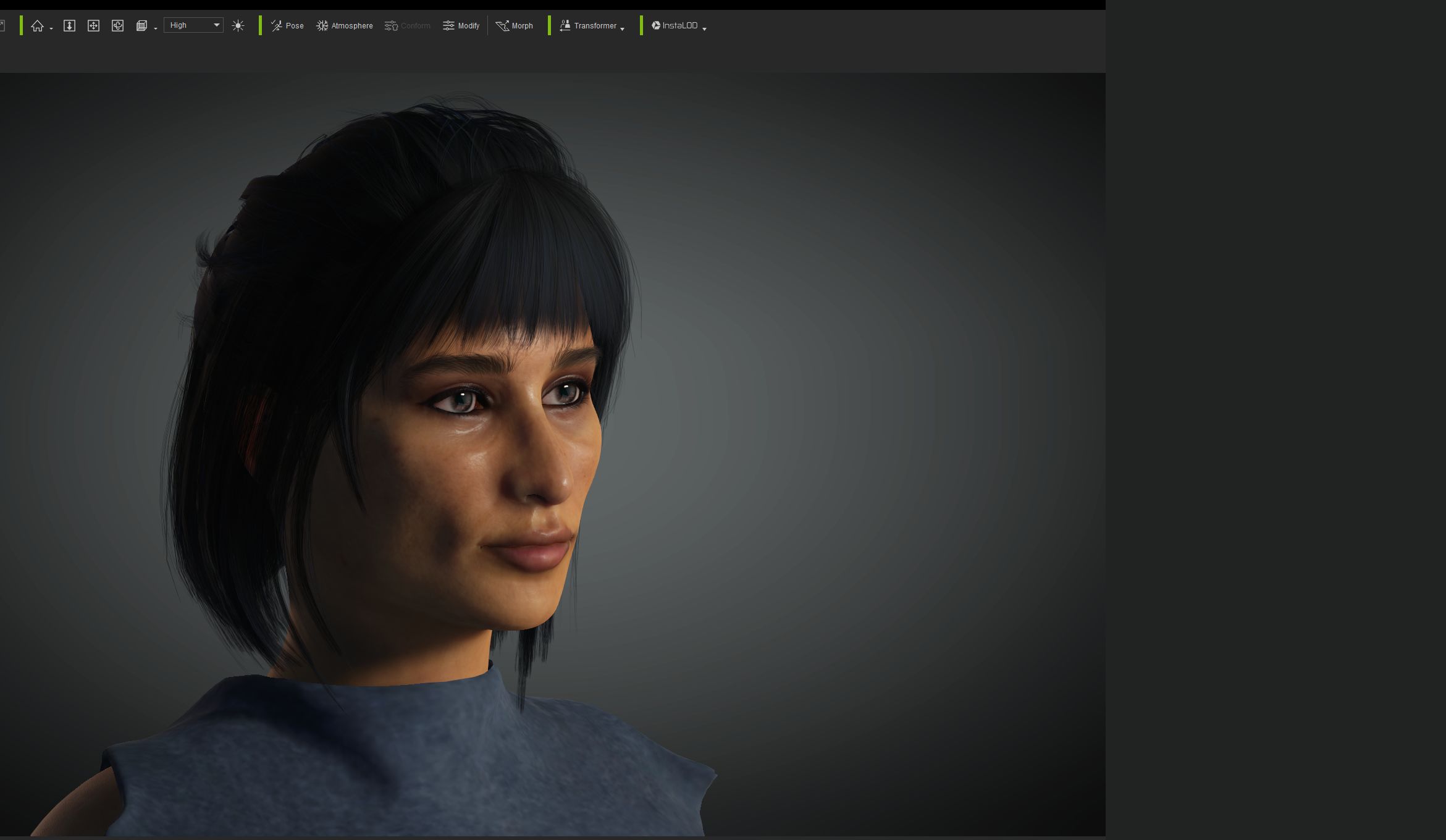

“The visual effects industry is interested in the physically accurate representation of the digital human, for example its hair, skin, and performance. But the sort of person who is represented as a digital human is almost always white and male. The algorithms used to create the ‘traditional’ digital human are centred around white Caucasian skin and straight hair. There is little primary research on how dark computer-generated skin operates under light, and computer-generated kinky hair hasn’t been modelled accurately. When we try to create a Black or brown digital human we are likely to end up with something that’s fundamentally incorrect,” she says.

Telling their own stories

Raqi started her career at Disney Animation Studios in California before emigrating to New Zealand. “I moved to Wellington and started working with Weta Digital, allowing me to learn from the best. The job is to support someone else’s story, not tell your own. While that was a key reason for me to move away from studio work, another equally important one was that when I looked around me I saw a majority of men. At that time there were no female VFX supervisors, so I saw no path forward.”

Storytelling is an important tool because it enables people to make sense of their world. “Initially, in my lighting class, we would buy digital assets from online marketplaces and light those. But then I started working with the students to create digital humans of themselves and to think like performers and cinematographers. The results were spectacular because students are far more invested in a story world they can inhabit. The digital human becomes a vehicle for autobiography and memoir and the student becomes an embodied VFX Designer.”

Inspiring future change-makers

Raqi believes that while the visual effects industry can’t be described anti-racist yet, change is coming.

“After George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter movement, I started wondering what anti-racist visual effects might be. Are the tools that we use equitable? How do we work across different disciplines within visual effects to enact that change quickly?

“We are experiencing a more vocal call for change in the industry but current power structures need to be dismantled. It’s exciting to see more early career artists hungry for this change. There’s an army of designers who work below the line in VFX—we can make meaningful change by enacting equity and diversity here, which will flow up into the studio system.

“The current generation is more active about advocating for change. They know the craft but they also embody the stance of a critical visual effects designer. The future of storytelling and visual effects must be anti-racist.”